St. Perpetua 2024–25 Computer Science Elective Trimester 2

Go to the latest lesson. See all classes.

Classroom and Self-Directed Learning Resources

- Mr. Briccetti’s YouTube Channel with many programming lessons for you to explore on your own

- MakeCode

- Block-based Programming Environments

- App Inventor

- MicroBlocks

- EduBlocks

- Blockly Games

- Snap!

- Run Snap!

- Snap! Reference Manual

- Snap! Crash Course

- “Why Do We Have to Learn This Baby Language?” from Brian Harvey, Teaching Professor Emeritus, University of California, Berkeley

- Python

- Trinket

- micro:bit Python editor

- Visualizing your Python program with Python Tutor Visualizer

- p5.js

- Tinkercad

- Beauty and Joy of Computing Curricula

- BJC Sparks for Middle School and Early High School

- BJC for High School (you are free to explore this if you run out of things to do in the middle school curriculum)

- code.org

- Zooniverse

- Teachable Machine

- Music

First Day, 2024-11-07

Welcome to Computer Science

Your Previous Computer Science Experience

Join Your Class in Google Classroom

Critical Thinking

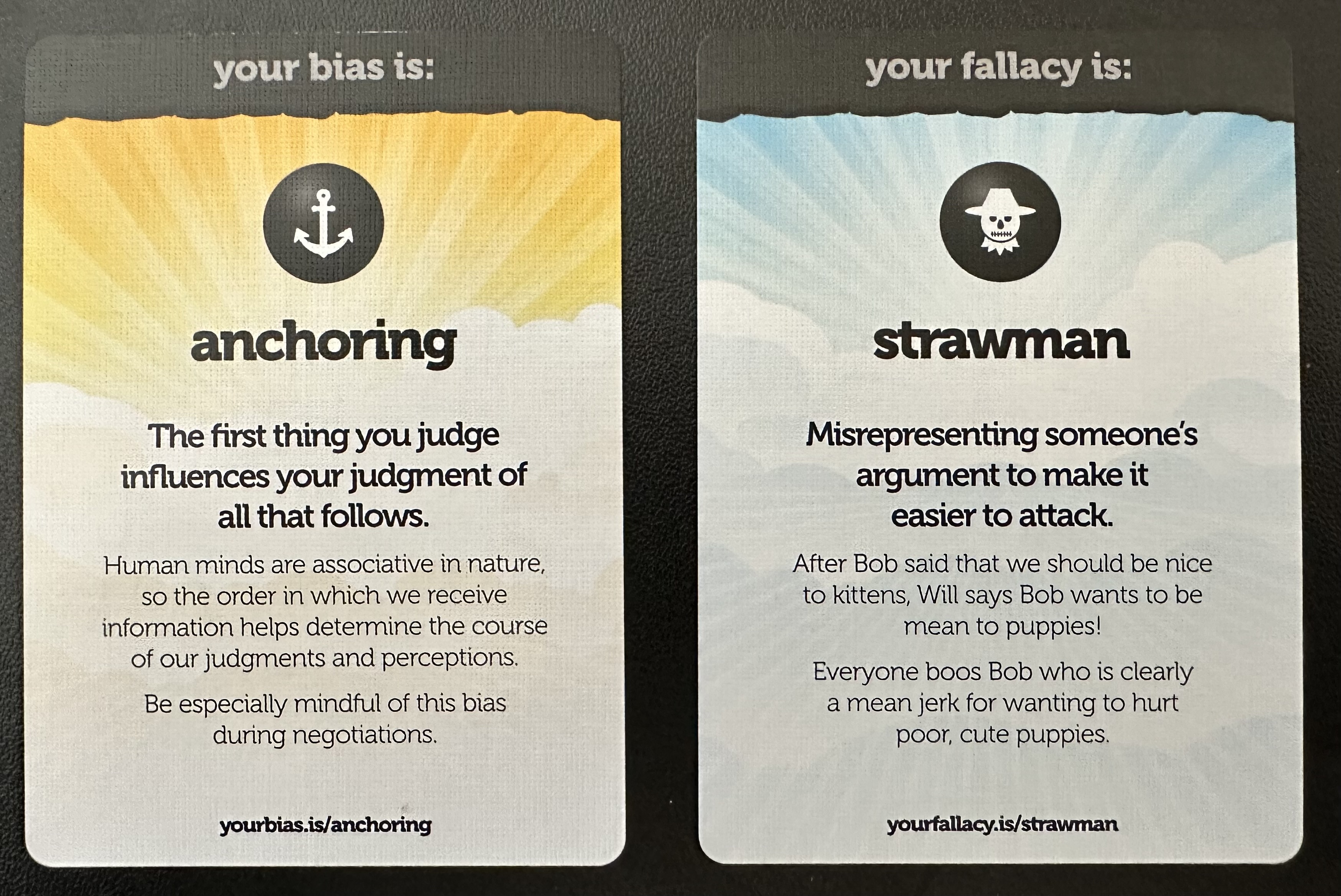

- Anchoring bias: The tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information encountered when making decisions.

- Strawman fallacy: Misrepresenting someone’s argument to make it easier to attack.

micro:bits and Smart Cutebot Cars

Self-Directed Learning Activities

See Resources at the top of this page.

2024-11-12

Computing in the News

Chinese Air Fryers May Be Spying on Consumers

Mr. B. Works on a Foursquare line fault detector

micro:bits and Smart Cutebot Cars

Self-Directed Learning Activities

See Resources at the top of this page.

2024-11-14

Critical Thinking

micro:bits and Smart Cutebot Cars

Car Links

Self-Directed Learning Activities

See Resources at the top of this page.

2024-11-19

Computing in the News

Pong Creator Al Alcorn is a Computer History Museum Fellow

micro:bits and Smart Cutebot Cars

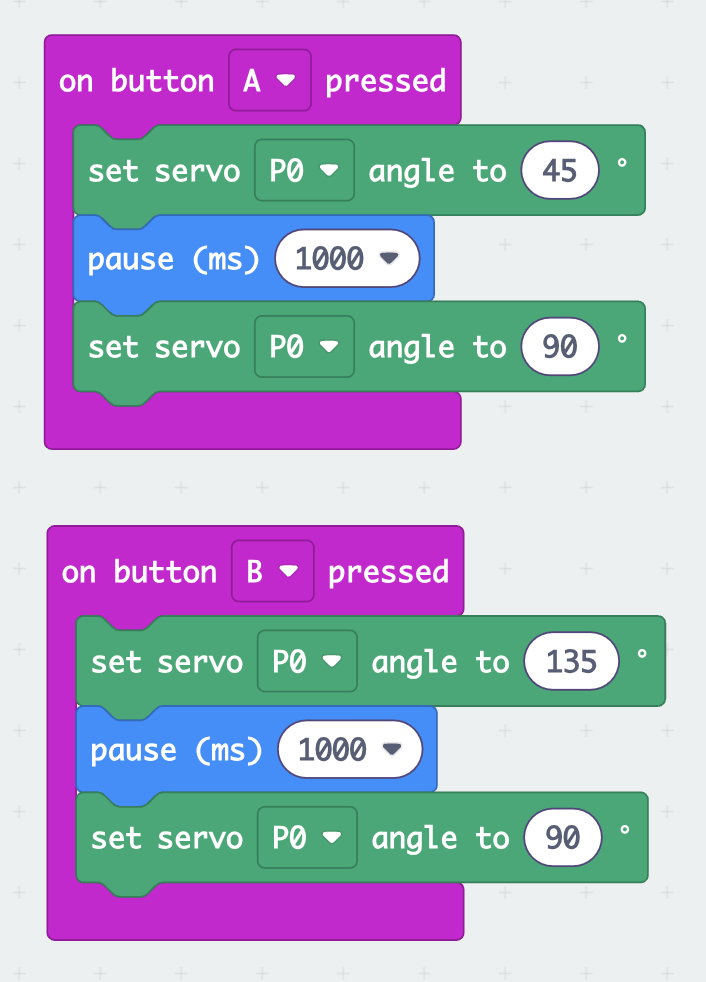

Controlling a servo motor

Self-Directed Learning

2024-11-21

Critical Thinking

Misleading Nature of “Earn as Much as $100 an Hour” Advertisements

Advertisements that use phrases like “earn as much as $100 an hour” can be misleading because they emphasize the maximum potential earnings without clarifying that this is not the typical or average income for most workers in that role. Here’s why this can be deceptive:

-

Selective Highlighting: The ad focuses on the highest possible earning scenario, which may only apply under very specific or rare circumstances. For example, earning $100 an hour might require achieving difficult performance metrics, working during peak demand hours, or taking on undesirable tasks.

-

Lack of Context: These ads often omit important details, such as how many people actually achieve the stated earnings, the average hourly pay, or the conditions required to earn that amount.

-

False Expectations: By presenting the highest earning potential prominently, the ad creates an impression that this level of income is common or easily attainable, which may not be the case.

How Anchor Bias Relates

Yes, anchor bias can play a role in these advertisements. Anchor bias occurs when people’s decisions or perceptions are influenced by an initial piece of information—the “anchor.” In this case, the “$100 an hour” serves as the anchor. Here’s how it works:

- Initial Perception: When potential applicants see “$100 an hour,” they are anchored to that number and may overestimate their likely earnings.

- Contrast Effect: Even if the ad later discloses the average earnings or lower starting rates, people may still judge the opportunity favorably because the anchor ($100) skews their expectations.

- Cognitive Shortcut: People might not analyze the details carefully and instead focus on the anchor because it is easy to remember and appears appealing.

Summary

These advertisements exploit anchor bias to make an opportunity seem more attractive than it might actually be. The “$100 an hour” figure sticks in people’s minds, even if it doesn’t reflect the typical experience. To avoid being misled, it’s important to look for disclaimers, average pay rates, and the conditions required to reach the advertised maximum earnings.

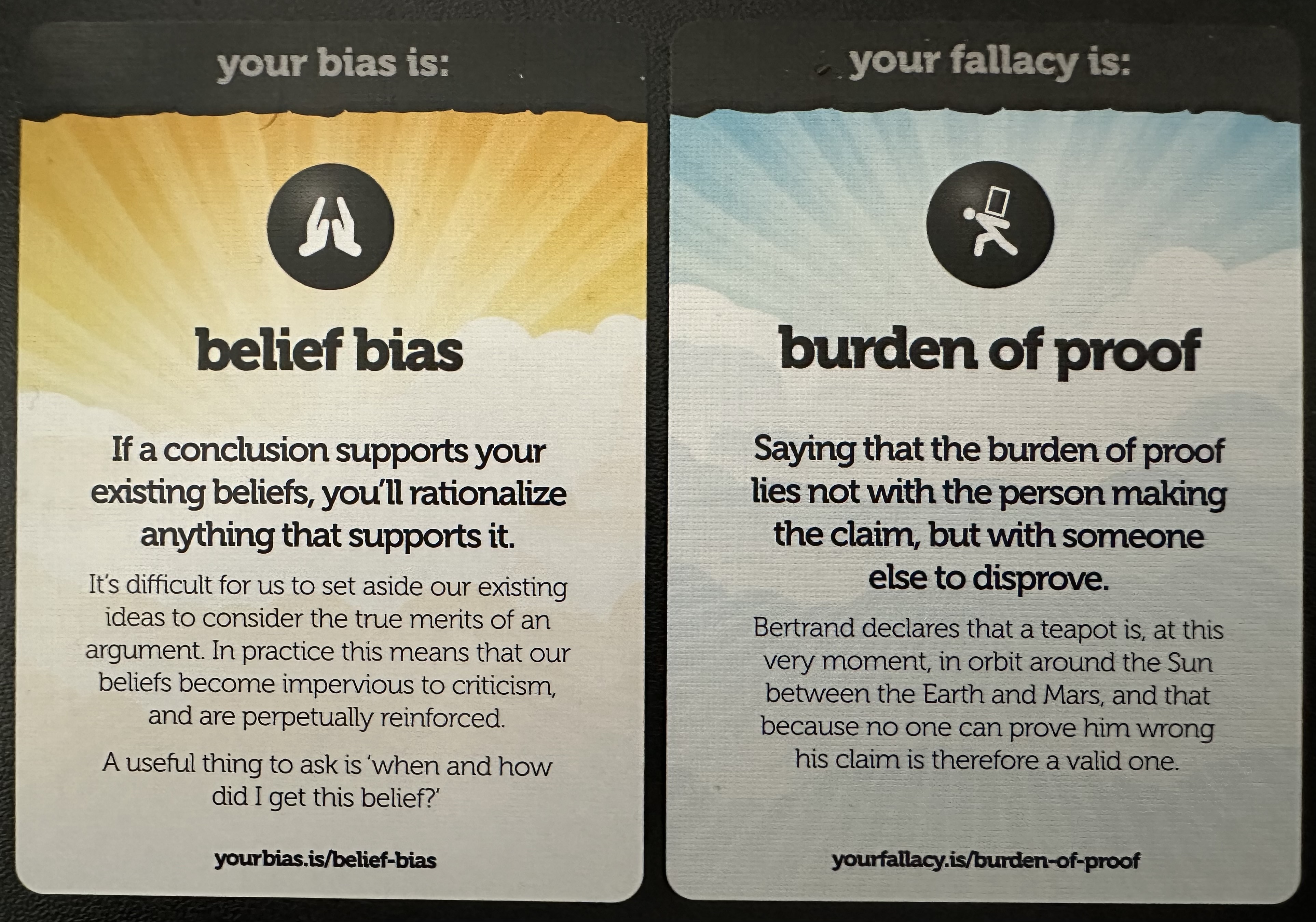

Quiz on biases and fallacies

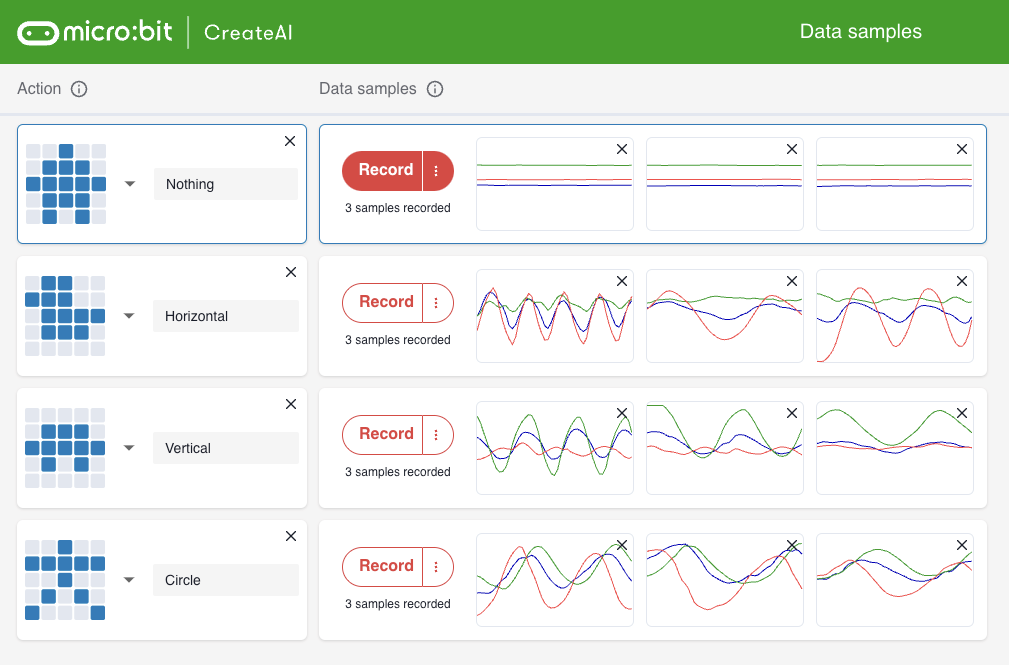

micro:bit CreateAI

Remember Google’s Teachable Machine? Now we can do something similar with the micro:bit.

Self-Directed Learning

2024-12-03

Computing in the News

Australia Bans Social Media Until Age 16

micro:bit CreateAI

Integrating with a MakeCode project

2024-12-05

Critical Thinking

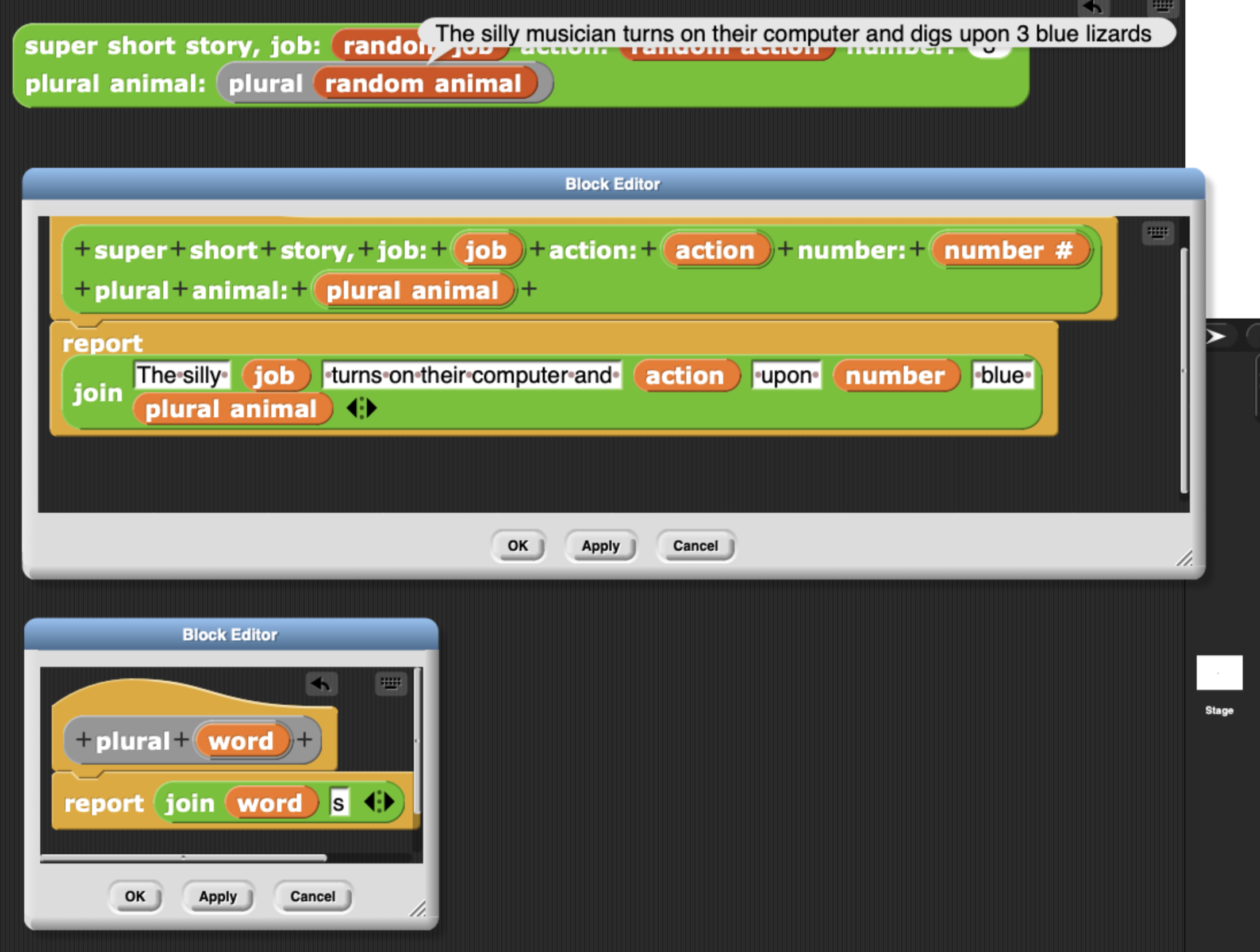

Here are some examples from ChatGPT:

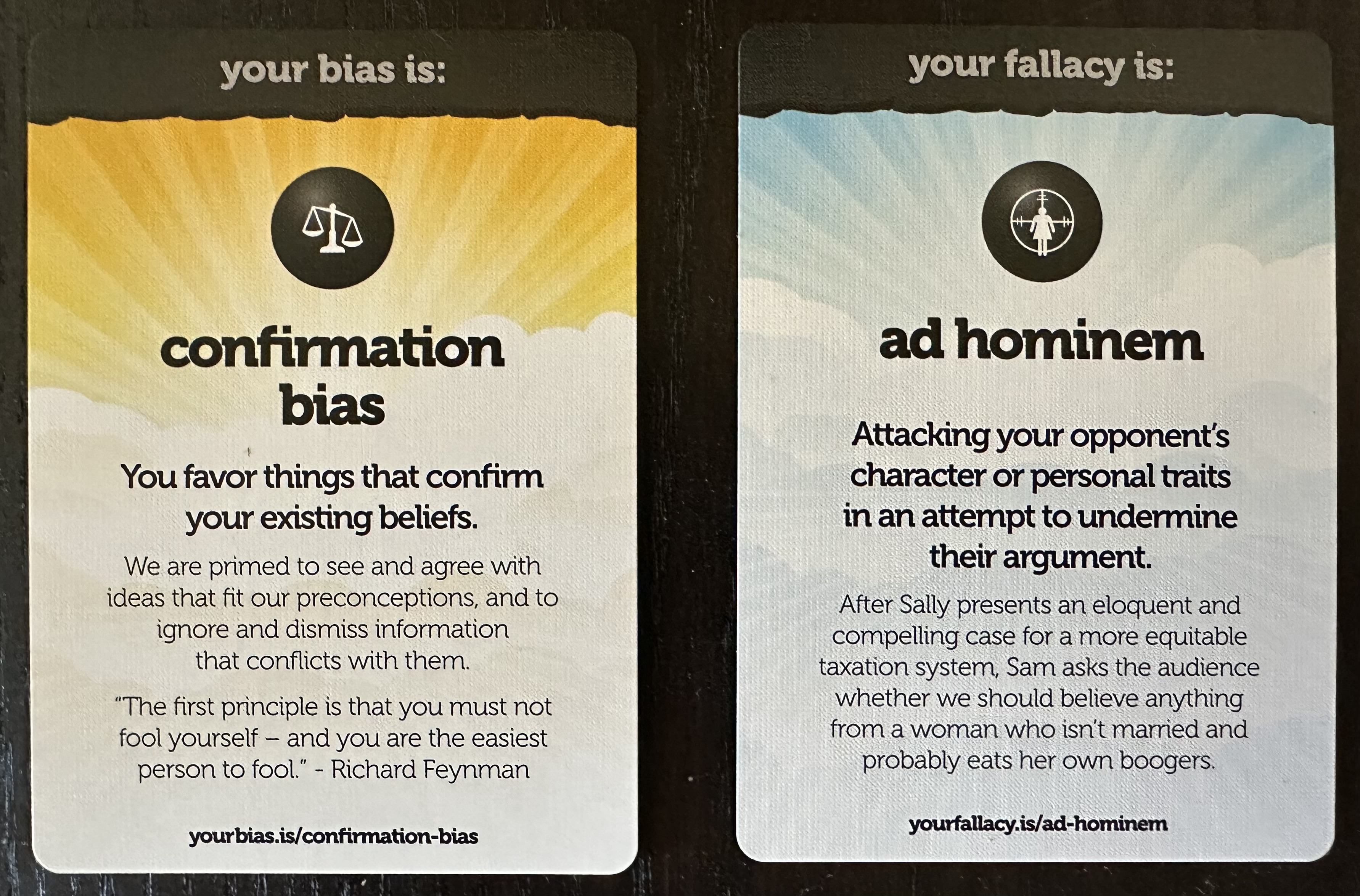

Belief Bias

Belief bias happens when someone thinks an argument is true or good just because they agree with the conclusion, not because the reasoning is logical.

Example:

- Belief: “Homework is bad for students.”

- Argument: “Homework is bad because it always makes kids stressed and doesn’t help them learn.”

- Why it’s a bias: You might agree that homework is bad, but the reasoning here isn’t strong—homework doesn’t always make students stressed, and it can help with learning. You believe the argument just because you like the conclusion.

Discussion Prompt: Can you think of an example when someone made a weak argument, but you believed it because you agreed with their conclusion?

Burden of Proof

Burden of proof means the responsibility to prove something is true. If someone makes a claim, it’s their job to provide evidence.

Example:

- Claim: “Our class will win the school competition because we’re the smartest.”

- Response: “That’s a big claim. What evidence do you have to prove we’re the smartest class?”

- Why it’s important: The person making the claim should provide facts or evidence, not just an opinion. Without proof, their claim might not be valid.

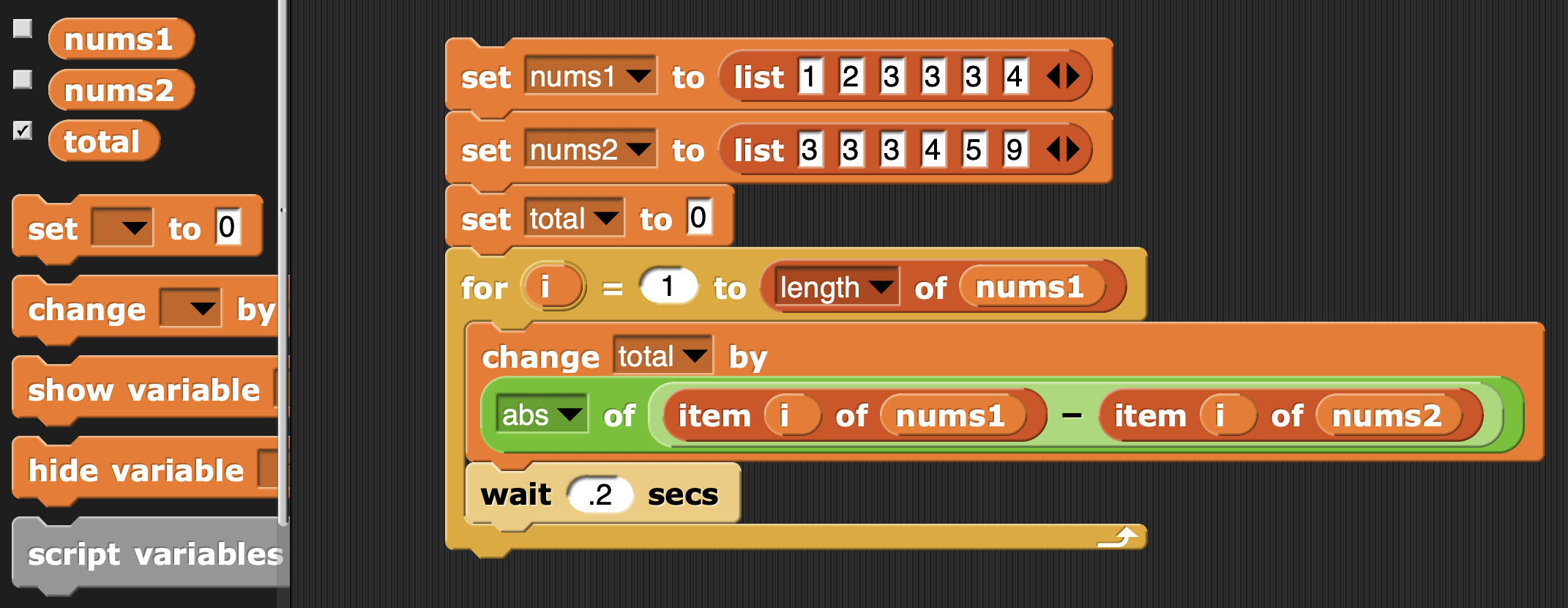

Advent of Code

From the web site: “Advent of Code is an Advent calendar of small programming puzzles for a variety of skill levels that can be solved in any programming language you like. People use them as interview prep, company training, university coursework, practice problems, a speed contest, or to challenge each other.”

Let’s solve day 1, part 1, using Python in the Python Tutor Visualizer.

One Possible Solution

nums1 = [3, 4, 2, 1, 3, 3]

nums2 = [4, 3, 5, 3, 9, 3]

nums1.sort()

nums2.sort()

zipped = list(zip(nums1, nums2))

total_dist = 0

for num1, num2 in zipped:

total_dist += abs(num1 - num2)

print(total_dist)

</a>2024-12-10

Computing in the News: Advent of Code

Solving Advent of Code Day 1, Part 1

Self-Directed Learning

2024-12-12

Critical Thinking

We’ll try a practice quiz on biases and fallacies from Gemini Advanced 1.5 Pro with Deep Research.

Advent of Code

Let’s solve day 7, part 1, using Python in the Python Tutor Visualizer.

2024-12-17

Computing in the News

- MacBook Pro screen on Vision Pro: Like two 5K displays in one.

- Mr. B. makes progress in Advent of Code

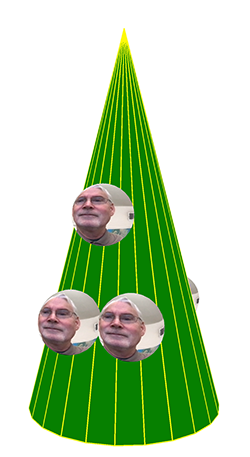

You on a Tree

The p5.js sketch

Benefits of concurrency in solving Advent of Code problems

Self-Directed Learning

2025-01-07

Computing in the News

Apple Vision Pro enthusiast Joseph Simpson teaches others

Beauty and Joy of Computing

University of California Computer Science Professor Dan Garcia

Photo of Snap! conference attendees

Self-Directed Learning

2025-01-09

Critical Thinking—False Dilemma

A false dilemma, also known as an either/or fallacy, occurs when someone presents only two options as the only possibilities, ignoring other potential alternatives. This oversimplifies complex issues and forces people into a choice that may not reflect the full range of possibilities. For example, saying, “You’re either with us or against us,” assumes there’s no middle ground or nuance, such as being neutral or partially agreeing with both sides. False dilemmas are often used to manipulate decisions by making one option seem much worse than the other. Recognizing this fallacy is important because it encourages critical thinking and helps people consider a wider range of solutions or perspectives.

In Arguments

“We either ban video games, or kids will never learn anything.” (This ignores the idea that video games can coexist with education.)

In Advertising

“Use our toothpaste, or your teeth will fall out!” (This ignores other brands or the possibility of good dental hygiene without their product.)

In Friendships

“If you don’t invite me to your party, you must not like me.” (This ignores other reasons someone might not invite a person, like limited space.)

In Politics

“We either cut taxes, or the economy will collapse.” (This overlooks other ways to address economic challenges.)

In Sports

“Either you’re a fan of our team, or you don’t know anything about sports.” (This excludes the possibility of liking other teams or being neutral.)

A Quick Look at Vision Pro Programming

Self-Directed Learning

Some of you may want to use this time to finish Tuesday’s assignment.

The micro:bits and CuteBots are here.

2025-01-14

Computing in the News

OpenAI’s new o3 model freaks out computer science majors

Apple Vision Pro enthusiast Joseph Simpson shows his cool spatial computing projects

Self-Directed Learning

2025-01-16

Critical Thinking

Bandwagon

The bandwagon fallacy occurs when someone adopts an idea, belief, or behavior simply because it is popular or widely accepted, without evaluating its merits. This fallacy plays on the desire to fit in and not be left out. For example, a student might start wearing a specific brand of shoes because “everyone else at school is wearing them,” even if they don’t actually like the shoes. Similarly, someone might claim that a movie is the best ever simply because it’s a box-office hit, without considering whether it aligns with their taste.

Examples:

- “You should get the new game everyone is talking about—it’s obviously the best!”

- “Everyone in class agrees that this project is too hard, so it must be unfair.”

- “If all your friends jumped off a bridge, would you do it too?” (classic bandwagon challenge)

Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc (False Cause)

The post hoc fallacy assumes that because one event happened after another, the first event must have caused the second. This ignores the possibility of coincidence or other causes. For instance, if someone eats a sandwich and later feels sick, they might mistakenly blame the sandwich without considering other factors, such as a stomach bug. This fallacy highlights the need for careful analysis before claiming causation. In English, it means, “after this, therefore because of this”.

Examples:

- “I wore my lucky jersey, and our team won the game. It must be because of the jersey!”

- “After we installed this new app, the computer started freezing, so the app must be the problem.”

- “I started drinking more water, and my grades improved—it must be the water.”

p5.js

function setup() {

createCanvas(400, 400);

colorMode(HSB);

background(0);

}

function draw() {

if (keyIsDown(32)) background(0);

noStroke();

const saturation = map(mouseX, 0, width, 0, 100)

const brightness = map(mouseY, 0, height, 100, 0)

fill(random(0, 359), saturation, brightness);

rect(random(0, width), random(0, height), 30, 30)

}

Self-Directed Learning

2025-01-21

Computing in the News

Bluesky, X Roll Out TikTok-Style Vertical Video Feeds

p5.js

Make a scene out of 2D or 3D shapes.

Self-Directed Learning

2025-01-23

Makecode for micro:bit

We’ll use Python to make a program that moves a pixel with tilting.

Self-Directed Learning

2025-01-28

Computing in the News

China heralds DeepSeek as a symbol of AI advancements amid U.S. restrictions

Tilting Pixel Game with MakeCode for micro:bit

![]()

Self-Directed Learning

2025-01-30

Cherry Picking Logical Fallacy

Multiplayer! Tilting Pixel Game with MakeCode for micro:bit

Self-Directed Learning

2025-02-04

Computing in the News

XGO Robot dog and XGO Rider appear at FOSDEM 2025

Get the Keys program with Snap!

Self-Directed Learning

2025-02-06

Critical Thinking

Let’s look at examples of:

- Straw Man Fallacy

- False Dilemma

- Ad Hominem Fallacy

- Motivated Reasoning

- Confirmation Bias

More Practice Cloning in Snap!

Self-Directed Learning

2025-02-11

CrunchLabs Sand Garden Hack Pack

Get the Items program with Snap!

Let’s add a power-up. Start with this program.

Self-Directed Learning

2025-02-13

Critical Thinking: Gambler’s Fallacy

The gambler’s fallacy is the mistaken belief that past random events can influence the probability of future independent events. It often occurs in games of chance, where people believe that if something happens more frequently than usual during a given period, it is less likely to happen in the future (or vice versa).

Example:

- In a fair coin toss, if heads has come up five times in a row, someone might believe that tails is “due” and more likely to appear on the next flip. In reality, each flip is independent, and the probability remains 50% for heads and 50% for tails.

Why It’s a Fallacy:

- The outcome of independent random events does not depend on past results.

- Each event has the same probability distribution as before.

- This misconception can lead to poor decision-making in gambling, investing, and other areas where randomness is involved.

Programming the Sand Garden

Assembling the Label Maker

Self-Directed Learning

2025-02-18

Computing in the News

No, 150-Year-Olds Aren’t Collecting Social Security Benefits, or, How Dates are Stored in Computers

Storing only 2 digits for the year led to the Y2K problem

How Python handles dates

We’ll write code in Edublocks to see how Python handles dates.

Self-Directed Learning

2025-02-20

Dangerous Programming Languages

Buffer Overflow

Self-Directed Learning

2025-02-25

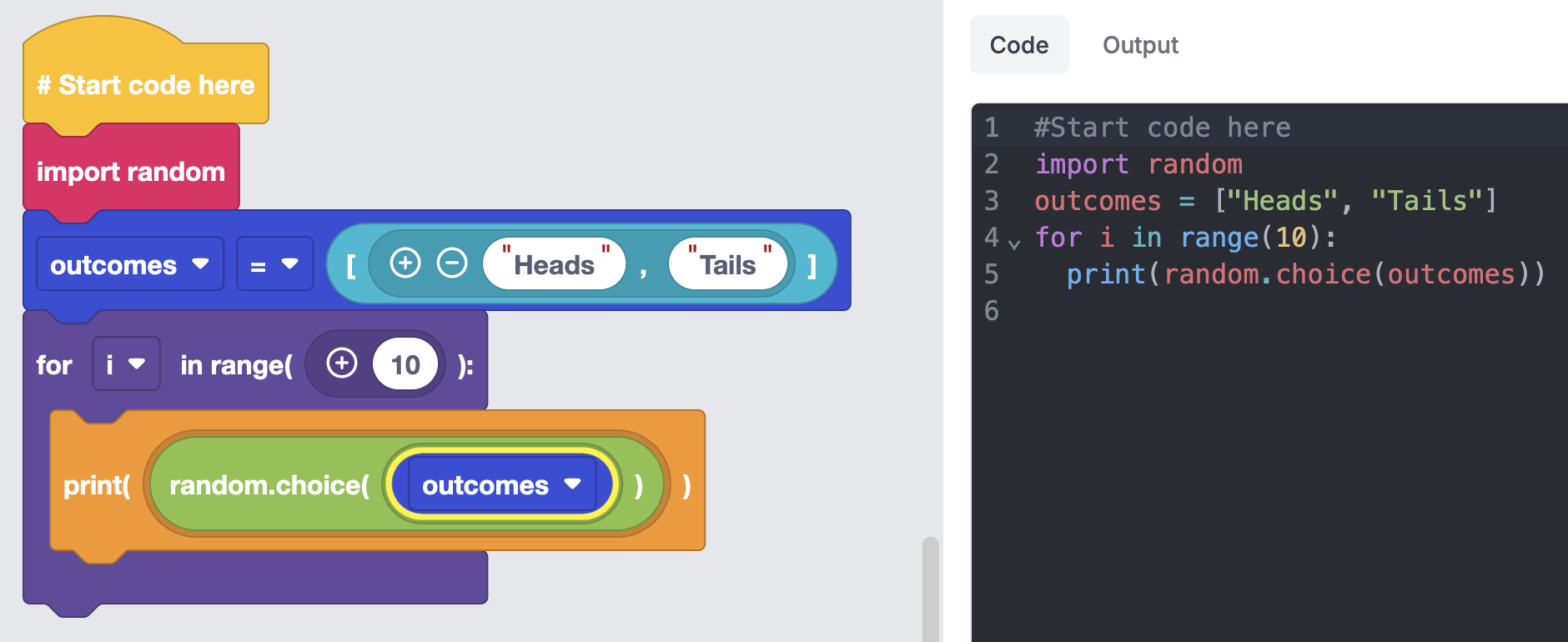

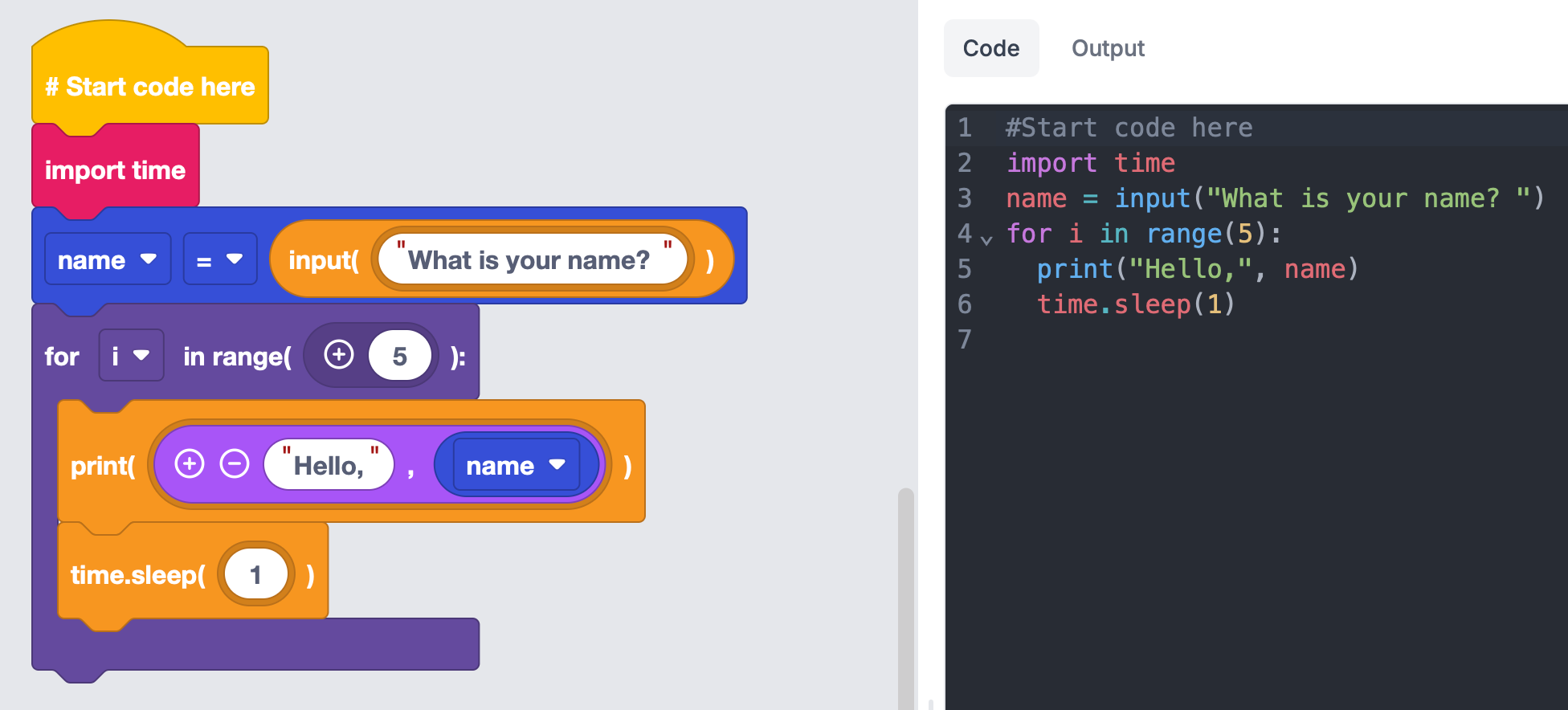

Python Programming with Edublocks

Random Coin Toss

Hello, Person

High/Low Guessing Game

Self-Directed Learning

2025-02-27

Critical Thinking: Loaded Question

From ChatGPT:

A loaded question fallacy occurs when a question is phrased in a way that assumes a controversial or unjustified premise, trapping the respondent into seeming to agree with something they might not actually believe.

Examples of Loaded Questions

- “Have you stopped cheating on tests?”

- This assumes that the person has cheated before, regardless of how they answer.

- “Why do you hate science?”

- This assumes that the person does hate science, even if they don’t.

- “Do you always make bad decisions?”

- This implies that the person regularly makes bad decisions, regardless of their answer.

How to Respond to a Loaded Question

- Call out the assumption:

- “That question assumes something that isn’t true.”

- Reframe the question:

- “If you’re asking whether I’ve ever cheated on a test, the answer is no.”

- Refuse the false premise:

- “I don’t hate science, so the question doesn’t apply to me.”

Python Programming with Edublocks

Make a program that simulates rolling two six-sided dice many times, and then displays how many times each outcome occurred.

from random import randint

counts = [0] * 13

for n in range(1000):

roll = randint(1, 6) + randint(1, 6)

counts[roll] += 1

for num, count in enumerate(counts[2:], 2):

print(f'{num} {count}')

We’ll also run the program with the Python Tutor Visualizer.